This is an expanded version of the presentation I gave on 4 October 2013 at the opening plenary session of the Society of City and Regional Planning Historians conference held in Toronto. Its purpose was to provide an overview of the planning history of Toronto in twenty minutes. It is loosely based on material discussed in my book Toronto: Transformation in a City and its Region, published by the University of Pennsylvania press on the same day. My book and this website provide details that lie behind the overview I offered in my presentation.

This is an expanded version of the presentation I gave on 4 October 2013 at the opening plenary session of the Society of City and Regional Planning Historians conference held in Toronto. Its purpose was to provide an overview of the planning history of Toronto in twenty minutes. It is loosely based on material discussed in my book Toronto: Transformation in a City and its Region, published by the University of Pennsylvania press on the same day. My book and this website provide details that lie behind the overview I offered in my presentation.

Click on illustrations for larger versions.

The Geographical Context

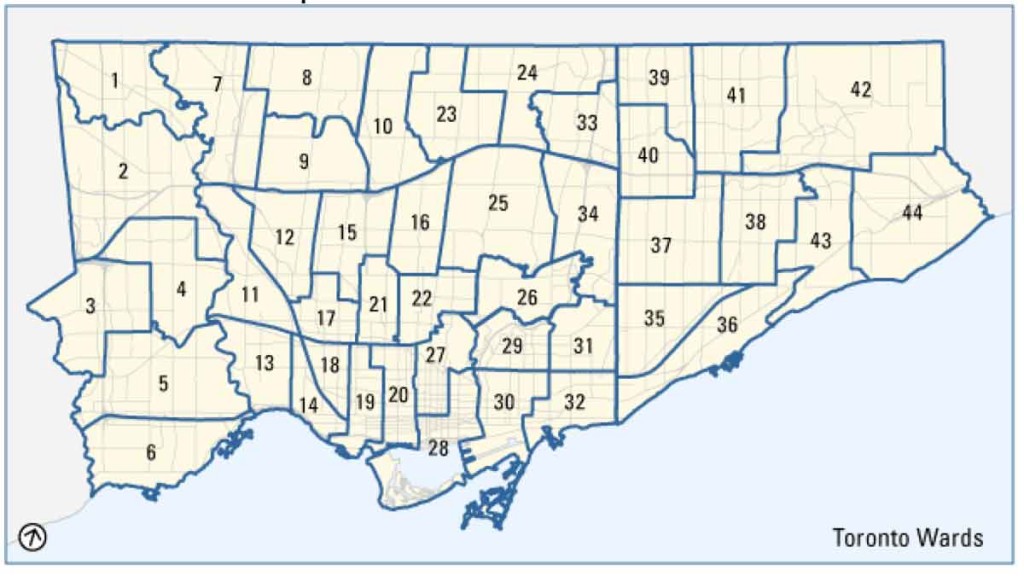

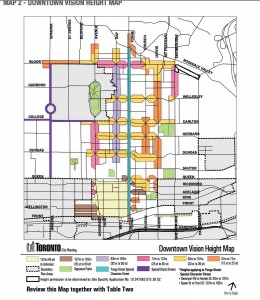

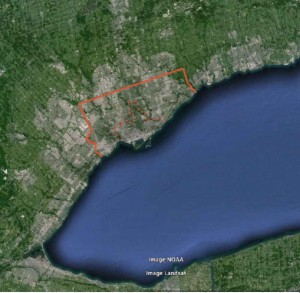

Some context is needed to make sense of my comments in this presentation. The red dotted line on this map shows the border of the old City of Toronto, the streetcar city that was built up by 1940. This no longer exists as a political entity even though for its citizens it remains a powerful reality, its urban landscapes are distinctive and it is widely admired for its street vitality and urbane qualities. In 1998, against almost universal popular opposition, the Province of Ontario amalgamated the old City with the other municipalities in Metro Toronto (outlined with the solid red line) to create the (new) City of Toronto.

Some context is needed to make sense of my comments in this presentation. The red dotted line on this map shows the border of the old City of Toronto, the streetcar city that was built up by 1940. This no longer exists as a political entity even though for its citizens it remains a powerful reality, its urban landscapes are distinctive and it is widely admired for its street vitality and urbane qualities. In 1998, against almost universal popular opposition, the Province of Ontario amalgamated the old City with the other municipalities in Metro Toronto (outlined with the solid red line) to create the (new) City of Toronto.

Between the border of the former old City (which has a population of about 650,000) and the new City (which has a population of about 2,600,000) are the inner suburbs. Outside the border of the new City are the outer suburbs. The grey on this Google image is the built-up or metropolitan area which has a population of about 6.6 million, which makes it the fifth largest metro in North America (after Mexico City, New York, Los Angeles and Chicago).

1. Unplanned Town 1793-1850: “A foul, disgusting, loathsome little capital” (Donald McLeod from Cleveland, 1841)

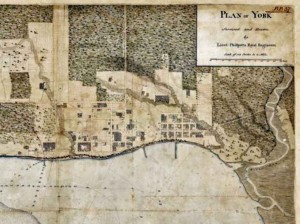

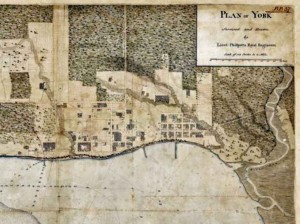

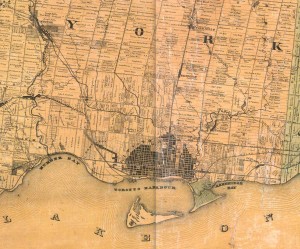

Toronto was founded in 1793 as a reaction to the American Revolution. The existing capital of Upper Canada at the mouth of the Niagara River on the south side of Lake Ontario, was too close to the Americans for comfort, and it was decided to move it here, where there was a protected harbour, hardly any native people, and endless forest. It might reasonably be expected that a new capital would warrant a small gesture in the town plan. However, as the map below (made in 1818, for the Town of York because the name had been changed) indicates, there was nothing of note done by the city fathers – just some uncoordinated grids. The broad strip on the left shows the initial clearing for Spadina Ave, an act of vainglory by a private landowner, an avenue of trees that would lead to his house on a hill a couple of kilometres to the north, that was never completed. It was a remote, messy little town of which little remains except the street patterns. So my first observation is that there was in fact no planning worth the name in Toronto until the 1940s – no grand avenues as in Washington, no Olmsted parks as in Buffalo and Boston, no city beautiful districts as in Cleveland. This may have been the reason for McLeod’s reaction, which was shared by many other early visitors. (I note that another presentation at this conference, by Michael McLelland, argues that the Simcoe Plan – named for the Lieutenant Governor who founded Toronto in 1793 and includes the two grids shown on this map – did create a distinctive plan of squares and spaces. My interpretation is that these are elementary forms that constitute planning only in its most trivial sense.)

But note on this map the line of Yonge Street (named for the English Secretary of War) running north through the forest, and the northernmost east-west street, which is Queen Street. Queen was the base line and Yonge was the primary axis for a regional land survey that established the foundation for settlement in this part of Upper Canada.

Unplanned Industrial City: 1850-1940

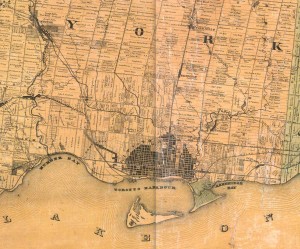

This map, made in 1860 (by which time the name had reverted to Toronto – York here refers to the County of York), shows how that regional survey had spread across the region as a megagrid of 1.25 mile squares, defined by side roads and concession roads. Though it was intended as a way to create farms, this became and remains a matrix for urbanization, with the roads turned into arterials and the squares forming patches in a giant urban quilt. This could be considered planning, but it is only in the most minimal sense of the word – providing a structure without any clear goals.

This map, made in 1860 (by which time the name had reverted to Toronto – York here refers to the County of York), shows how that regional survey had spread across the region as a megagrid of 1.25 mile squares, defined by side roads and concession roads. Though it was intended as a way to create farms, this became and remains a matrix for urbanization, with the roads turned into arterials and the squares forming patches in a giant urban quilt. This could be considered planning, but it is only in the most minimal sense of the word – providing a structure without any clear goals.

The1860 map shows the first signs of industrialization – the railways that cut across the grid and along the lakeshore, separating the city from Lake Ontario, a problem still not fully resolved. Factories soon located near the railway lines, and by 1880 Toronto was a significant Great Lakes manufacturing city. It was committed to laissez-faire capitalism, the rivers and harbour were regarded as open sewers, and the city grew out in mini-grids intended to be efficient and profitable, packed with houses yet with the fewest possible civic amenities. Most parks, for instance, are small and were the result of bequests rather than generosity of spirit by Toronto’s politicians.

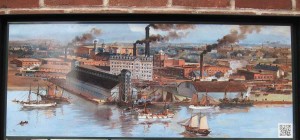

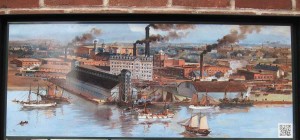

A bird’s-eye view of Gooderham and Worts distillery in the 1880s (now the Distillery District, a pedestrianized artist/tourist/heritage area), shows the smoking chimneys and air pollution that symbolized prosperity and progress in industrial Toronto.

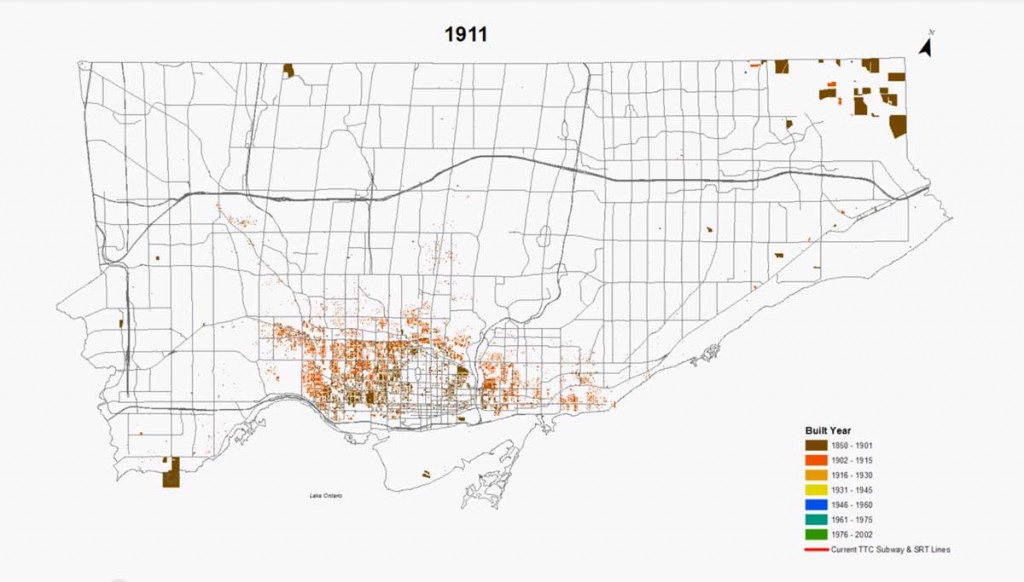

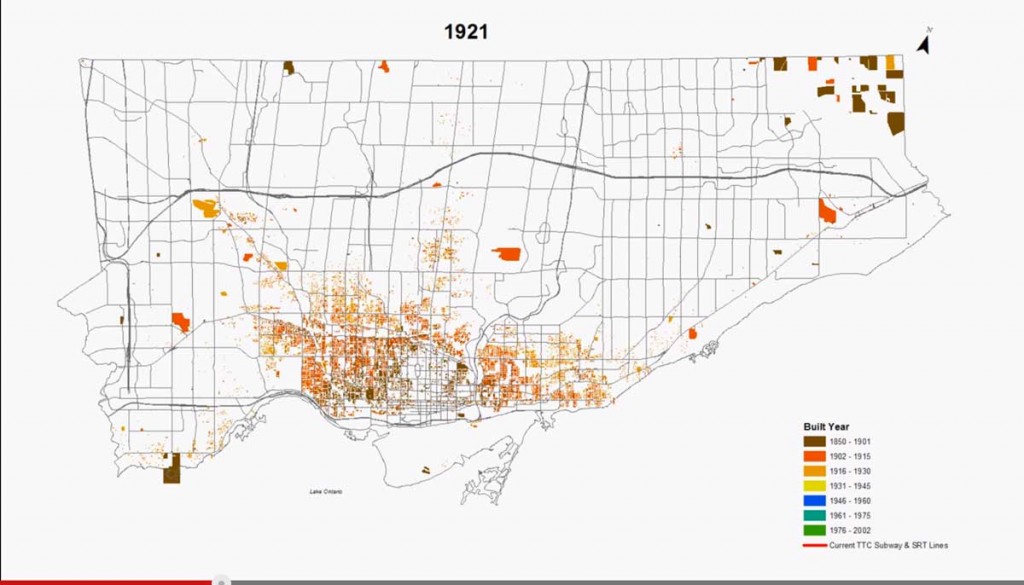

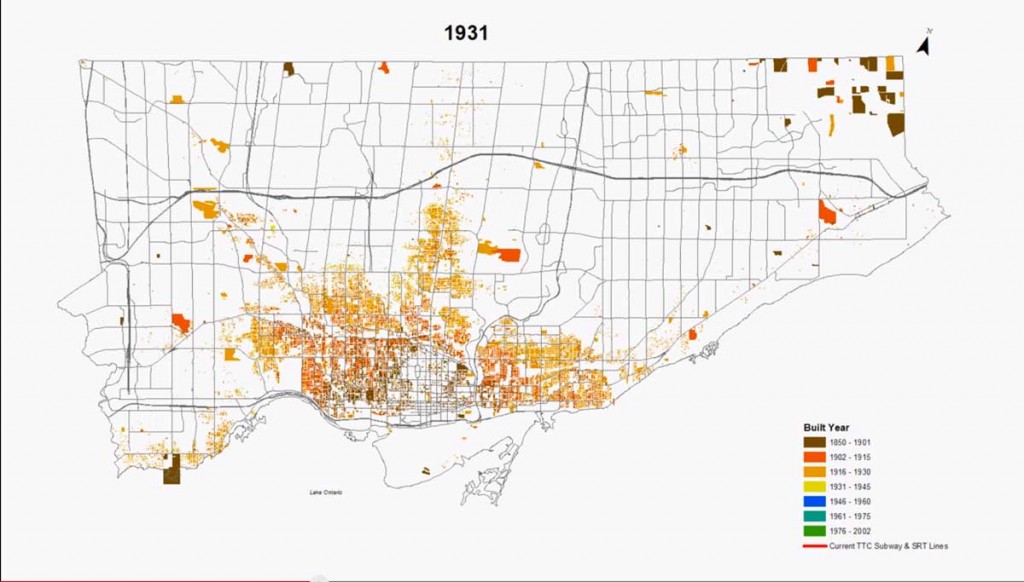

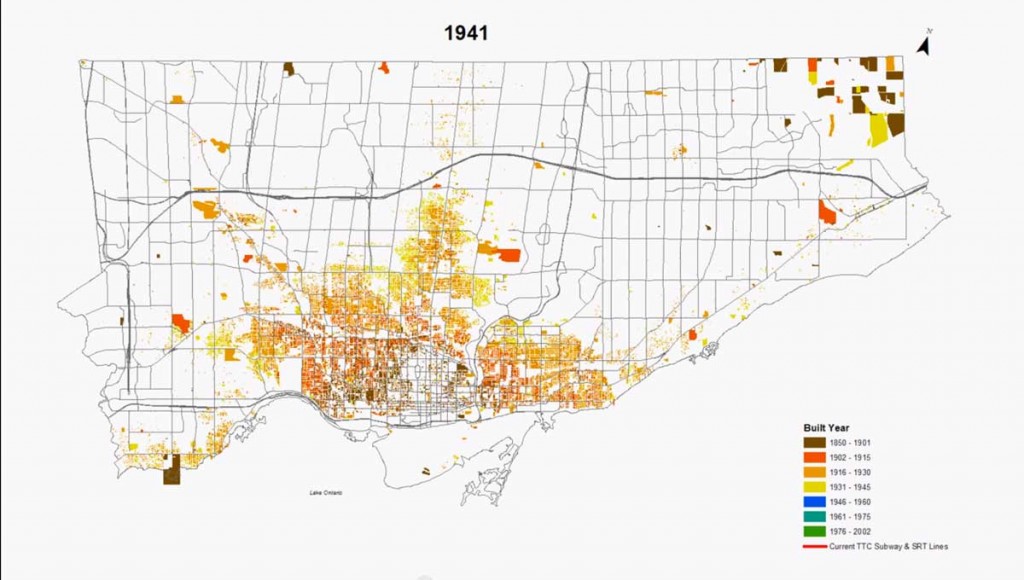

An Accidental Success – Streetcar City 1870s-1930s

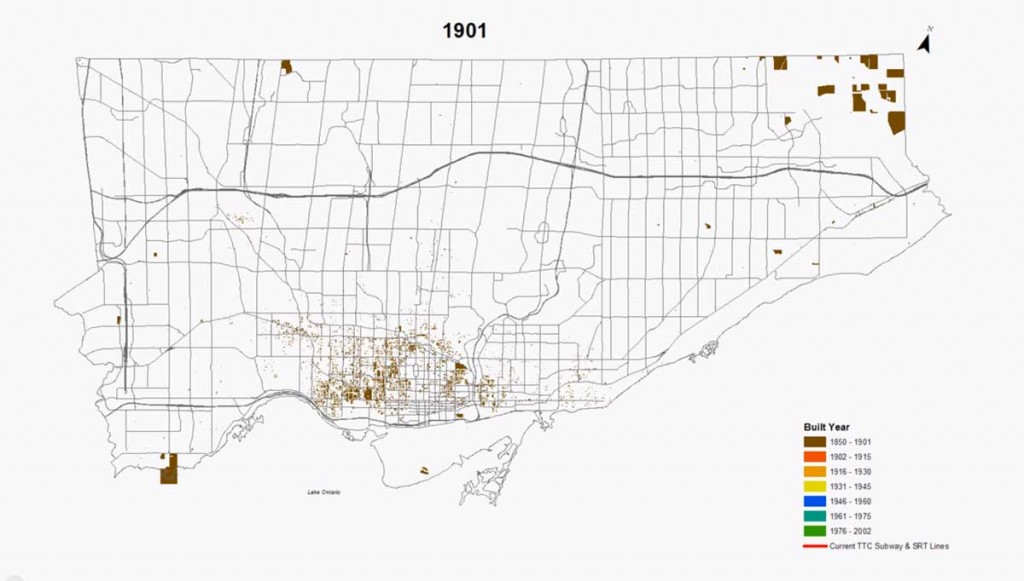

Industrial Toronto expanded in concert with streetcars and this created a distinctive urban form. My second comment is that even though that expansion of the industrial city occurred without any planning or forethought other than dividing it into profitable lots, the result is a streetcar city that has to be regarded as a great accidental success. The network of streetcar routes developed as continuous main streets, lined with commercial blocks of two and three storeys divided into shops with 20 or 40 frontages. Behind them densely packed houses lined mini-grids of residential streets within easy walking of the streetcar lines. The styles and details changed, especially after 1900 with electrification and shifts in architectural fashions, but the basic urban form spread until the 1930s when the streetcar city of old Toronto was fully built-up to its borders.

On the left is a typical streetcar main street (Queen West in Parkdale in 2010). On the right at bay and gable streetcar houses – a distinctive Toronto style. Both date from the 1880s, and the buildings are brick because a by-law banning wood structures had been passed earlier in the century following a serious fire.

These streetcar urban forms have proved to be extremely adaptable and resilient, in some cases surviving to the present almost unchanged, and in many cases renovated, infilled and gentrified. They epitomize the current ideal of a pedestrian and transit oriented city. They are a major reason why Andres Duany claims that Toronto has more street-oriented retailing than all the sunbelt cities put together, and it was into a streetcar neighbourhood that Jane Jacobs chose to live when she moved to Toronto in 1968.

Planning Begins

From 1793 to 1940 what little formal planning there had been in Toronto was the work of private landowners, either laying out avenues such as Spadina and University leading to their buildings, or leaving a patch of land for a park (Grange Park). City politicians seemed to have been interested only in utilitarian approaches, and grids provided an easiest and most efficient way to lay out new developments – to paraphrase Lewis Mumford – any city clerk could do it.

The plan that ended this long drought was this one – prepared in 1943 by an advisory board to the old City as a plan for postwar growth of Toronto. It is significant because it is for a metropolitan area – far beyond the aegis of the old City, because it is envisaged a future based on cars not streetcars (and in fact shows a redevelopment area in the central city that would have included most of the 1880s streetcar neighbourhoods), and because it shows a number of suburban communities. The network of dark lines are “superhighways” – at the time only one, the Queen Elizabeth Way in the bottom left, had been built; there is also a network of arterials following the megagrid of the regional survey.

There were no tools to implement any of these proposals at the time, but those came after the war and many aspects of this plan, including several expressways, did creep into subsequent thinking and were implemented

There were no tools to implement any of these proposals at the time, but those came after the war and many aspects of this plan, including several expressways, did creep into subsequent thinking and were implemented

Metropolitan Toronto

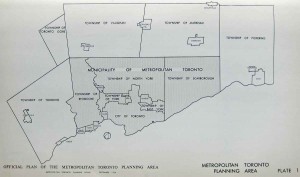

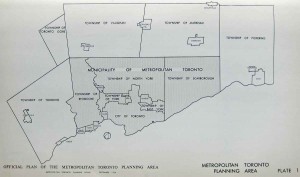

There was an international flurry of planning legislation following the Second World War. In Ontario the first effective town planning act was passed in 1946 (under the Canadian constitution provinces have full authority over cities and municipalities). Previous acts had few teeth, but this act required municipalities to prepare official plans and provided the legal means to enforce them. Then in 1954 the province created the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, covering the area shown in the 1943 plan, to oversee regional growth.

Metro consisted a two-tiered system of government that combined the old City of Toronto with adjacent townships. Metro was the superior body and responsible for coordinating development and planning across all the local municipalities, which did retain control over local development issues. Metro, for instance, was responsible for managing expressways and arterial roads, the lower tier municipalities were responsible for local streets and roads. Metro was also given subdivision controls for townships adjacent to its borders, a measure that ensured efficient servicing throughout the urban region and prevented leapfrog developments.

Metro consisted a two-tiered system of government that combined the old City of Toronto with adjacent townships. Metro was the superior body and responsible for coordinating development and planning across all the local municipalities, which did retain control over local development issues. Metro, for instance, was responsible for managing expressways and arterial roads, the lower tier municipalities were responsible for local streets and roads. Metro was also given subdivision controls for townships adjacent to its borders, a measure that ensured efficient servicing throughout the urban region and prevented leapfrog developments.

Metro was a system of urban government that was widely admired in North America and was copied in some American cities, such as Minneapolis. Here it lasted until amalgamation in 1998, though its political clout was diminished after about 1970.

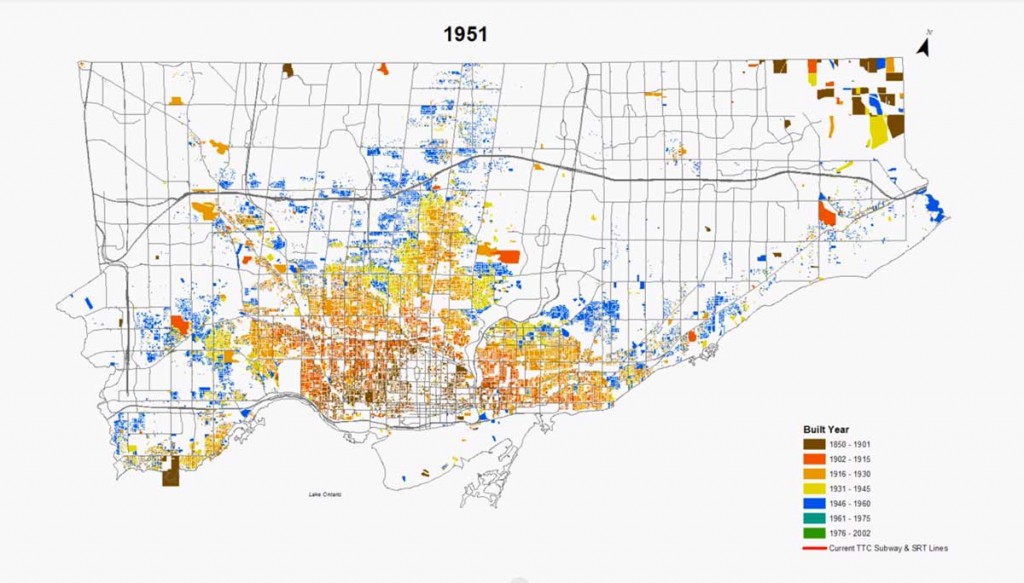

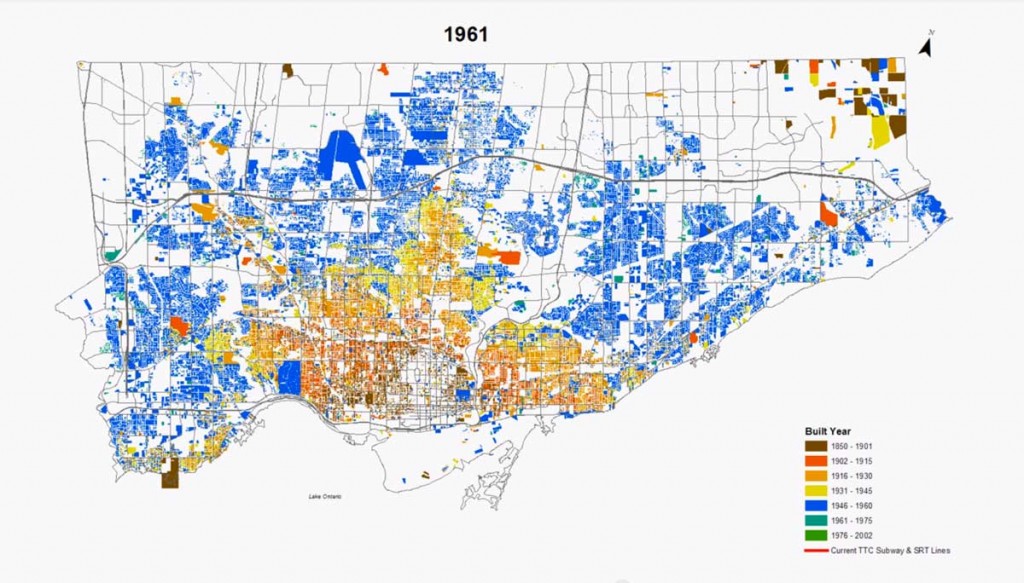

Metro’s Work

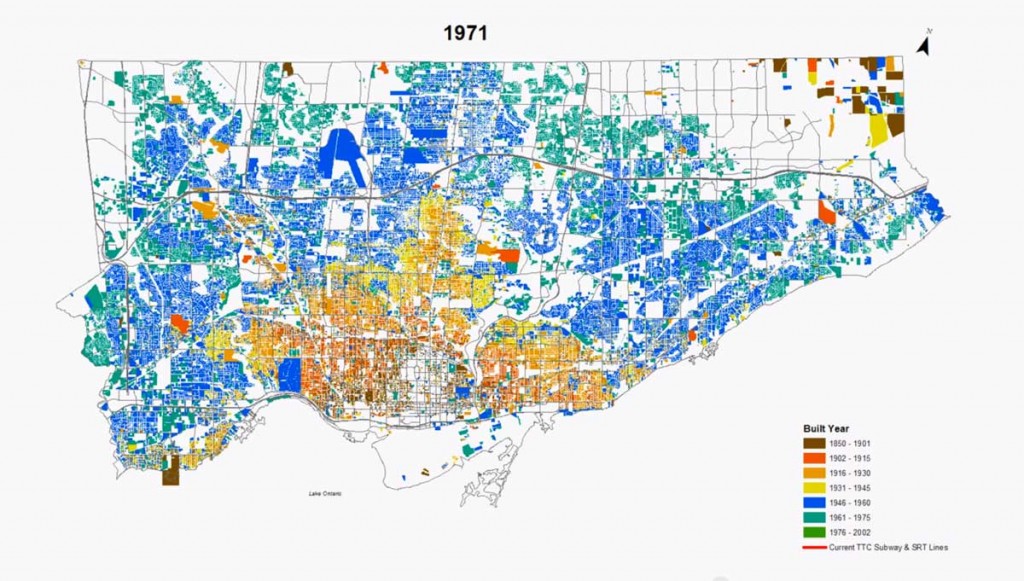

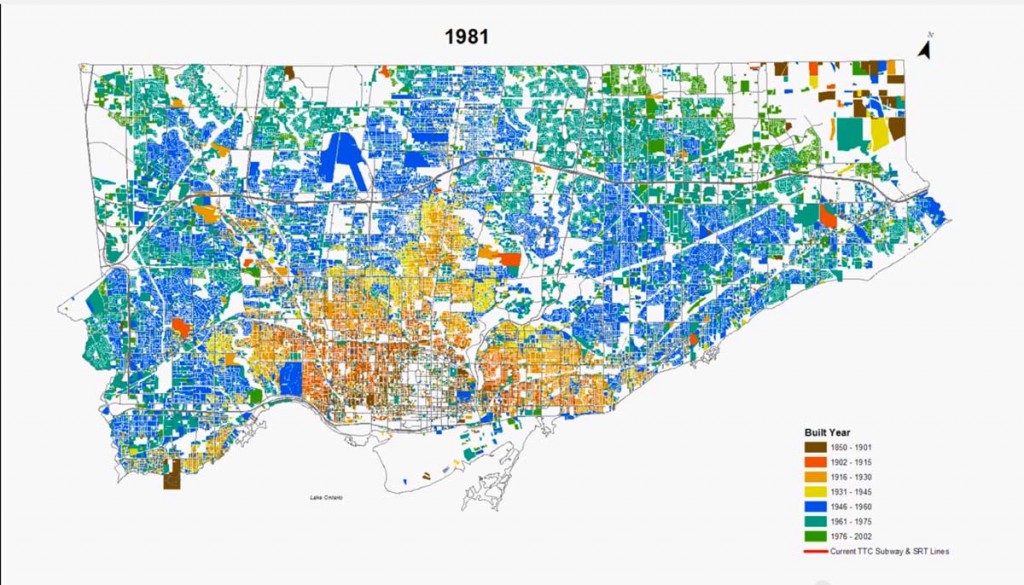

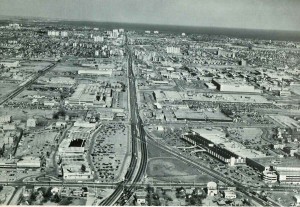

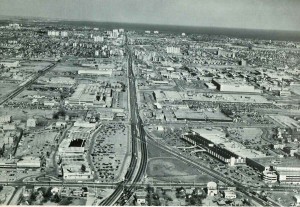

Metro was a powerful and reasonably enlightened, albeit very utilitarian institution. Although its long-term plans called for widespread redevelopment in the central city, it never got to those, probably because it was so busy managing suburban growth. And, unlike what happened in many U.S.cities at that time, it did nothing to undermine the streetcar system, and in fact oversaw the construction of the first subway lines here. Since the old City was full, most of Metro’s work handling growth was in the suburbs, and there a lot of what it achieved is not that exceptional – commercial strips, plazas, malls, employment districts, neighbourhood units, all the familiar elements of North American post-war, automobile oriented suburbs, can be found in Toronto’s inner suburbs. This air photo of Eglinton Avenue from 1969 shows all of these, stretching from the Don Valley to Lake Ontario.

But there was one major difference. Metro required the use of apartment towers in residential areas to increase densities in order to support bus transit, and to provide a mix of housing types. Clusters of these can be see in the distance in the photo on the left, and they were usually grouped in clusters of 4 to 6 – not more because Metro planners did not want to create apartment ghettoes. Some of the towers were social housing, but many were private rental. Hundreds of 14 and later 22 storey towers, mostly slabs, were built between 1955 and the early 1970s, when their construction became uneconomic. So my third comment is that while the modernist planning era of Metro Toronto ushered in a radical change in the way the city was made, the otherwise unremarkable results are exceptional in North America (with the possible exception of Montreal) because of its landscape of apartment clusters in the inner suburbs. These are a major reason why skyscraperpage.com ranks Toronto second in the world after New York City for the number of skyscrapers over 12 storeys.

Revitalization of the old Streetcar City

Metro ruled the roost until about 1970, managing suburban growth, building expressways (the Don Valley Parkway and the Gardiner), upgrading services, financing subway construction. Its ideological superiority ended about 1970 when the Spadina expressway, already under construction in the north-west suburbs, ran into a major political protests by residents of the old City, where it would have destroyed streetcar neighbourhoods near the University. The expressway was stopped by the province. This in itself is not unusual in North America, a number of cities have expressway stubs, but in Toronto it shifted the planning and political balance to the old City which became quickly and increasingly aware of the value of the forms of the streetcar city, something that had not hitherto been regarded as obvious. My fourth set of comments has to do with the way that the old city has been revitalized and changed its identity since then.

These photos are both of Bloor West near Brunswick Avenue (and where Jane Jacobs lived) – the one on the left from 1969 or 1970, the one on the right from 1992. In 1970 the Bloor subway had already replaced streetcars here but this gives a sense of drabness, buildings still covered with industrial grime, poles and wires, sidewalks were strictly for walking, as was true of all the main streets. By 1992 the wires had gone, there were trees in planters, sidewalk sales and cafes – the streetcar city was being celebrated in daily life.

A key to this revitalization was a concerted effort by old City planners and politicians to maintain the population of the central area at a time when US rustbelt cities were experiencing rapid hollowing-out as a result of deindustrialization. St Lawrence Neighbourhood, just east of downtown, was the flagship project for this in the 1980s. It is a mixed income, mixed ownership (from fully subsidized to fully owned), mid- and low-rise, social housing project for about 10,000 people. It was built on former industrial sites next to the railway. Unlike the superblock urban renewal projects of the 50s and 60s, this was street-oriented (in fact it extends some of the streets in the first 1793 plan). There are schools and parks, and families want to live here. Similar but smaller projects were built elsewhere in the old city, and they are a major reason why Toronto’s central area population did not decline.

The photo on the left shows the rectangular blocks of St, Lawrence in the middle-right, next to the railway. The townhouses are in the centre of those blocks. The basic form has been copied in several adjacent developments.

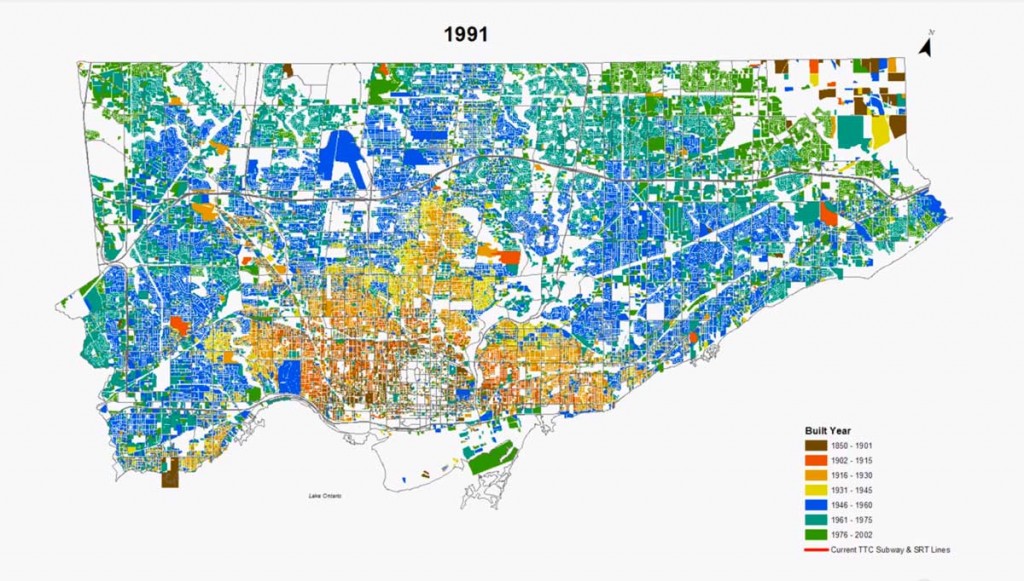

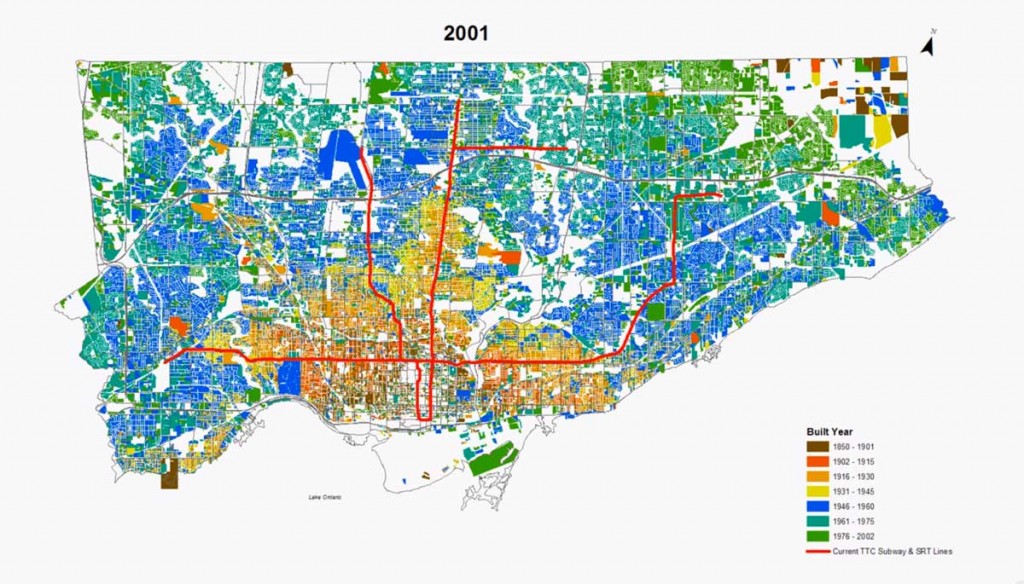

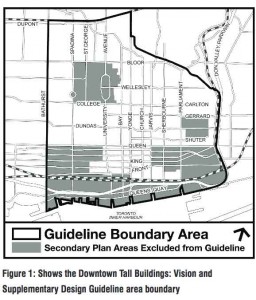

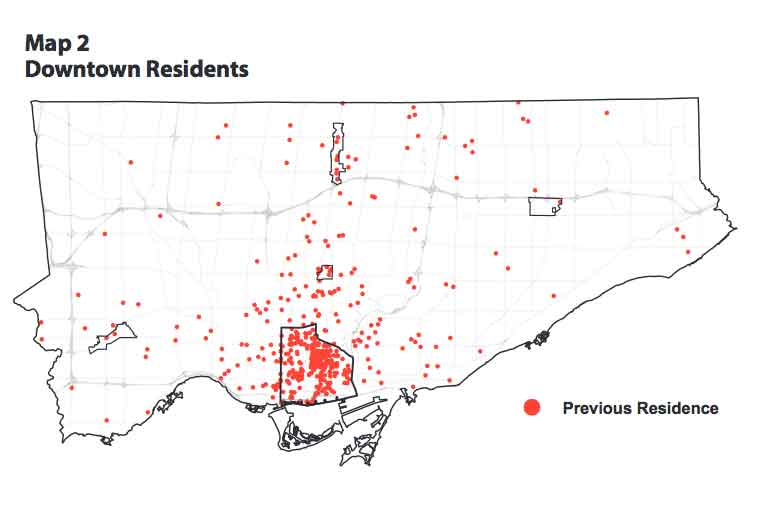

In the early 1990s provincial and federal governments withdrew subsidies for social housing, so planners in the old City rethought their strategy by removing restrictive zoning in two obsolete commercial/industrial areas on either side of downtown (known as the two kings because they were centred on intersections with King Street). Private developers seized the opportunity to build condominiums, beginning a boom in condominium construction that continues to the present. At first the buildings were quite modest and limited to those two areas, but they now reach skywards and have spread throughout most of the new City of Toronto and into the outer suburbs. This boom has contributed to an increase in the central area population, which since the late 1970s has grown by well over 70,000, and this has in turn contributed to revitalization of the streets and institutions in the core of the old city.

Except for the cluster of office skyscrapers behind the CN Tower almost every tall building in this 2012 photo is a condominium, along the lakeshore and off into the distance.

Diversity of the Outer Suburbs

My fifth set of comments are to do with the growth and diversity of the outer suburbs.

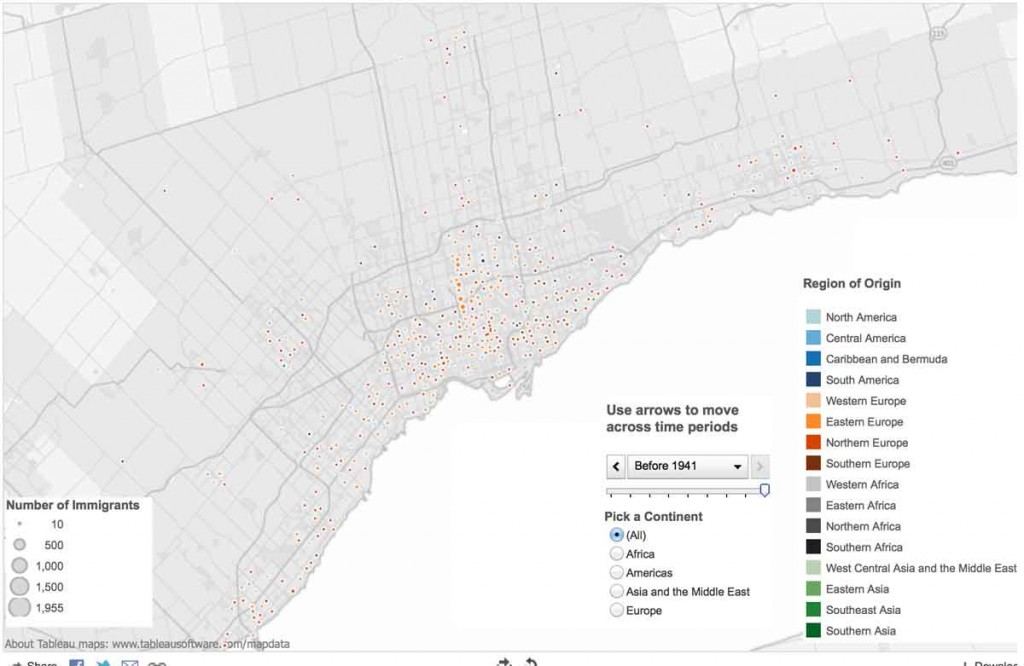

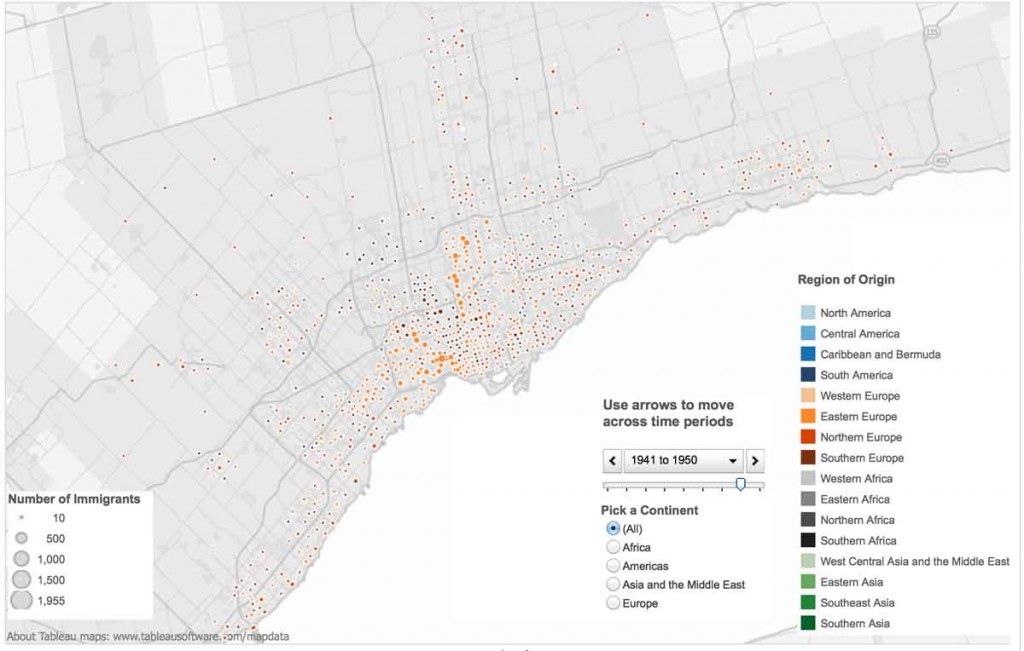

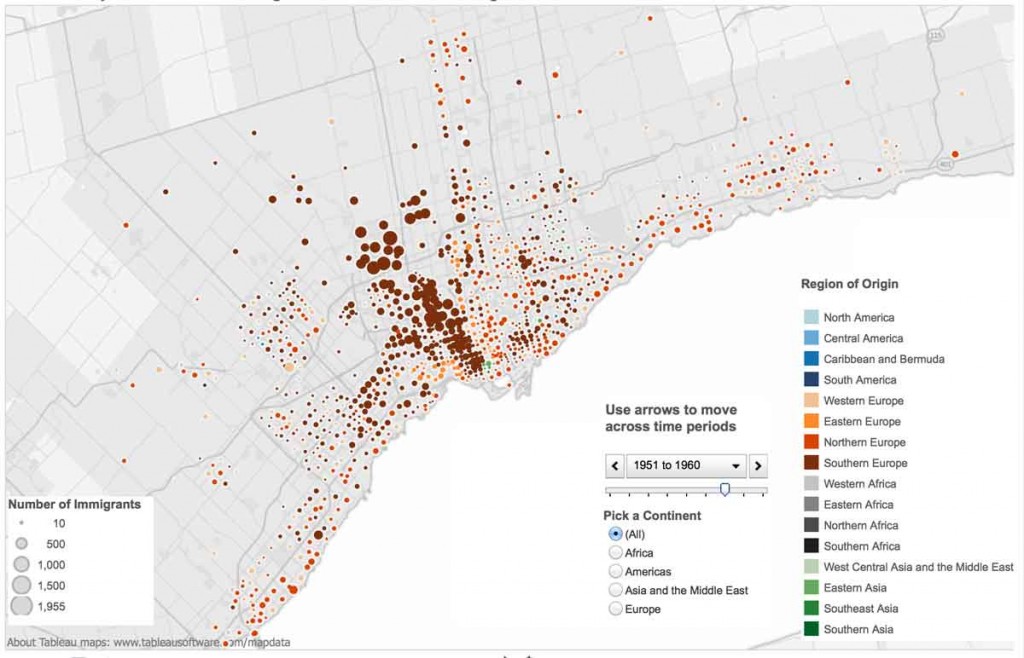

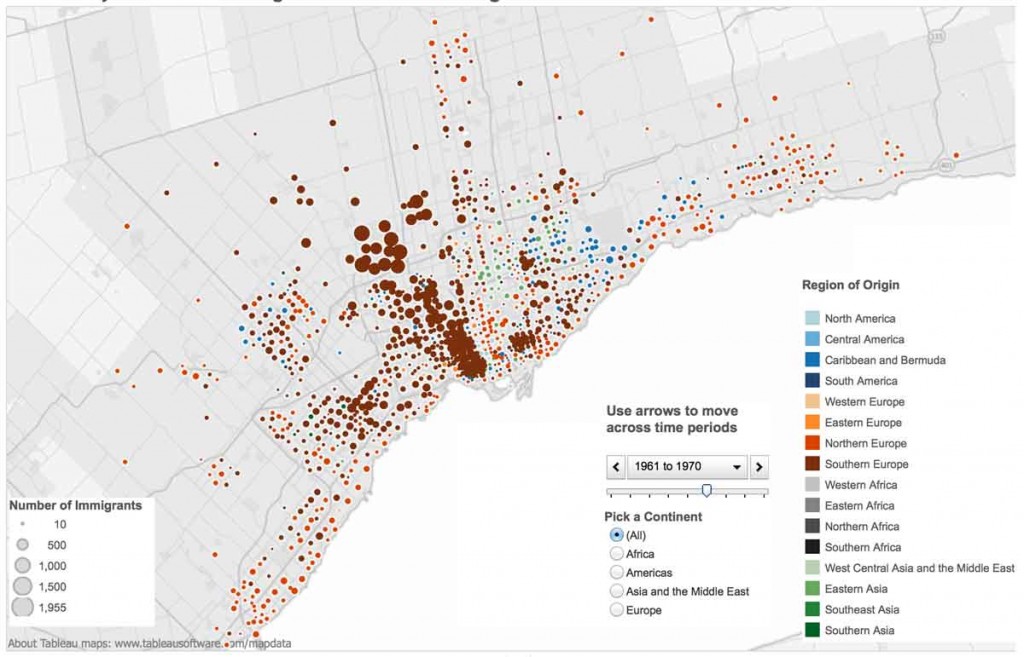

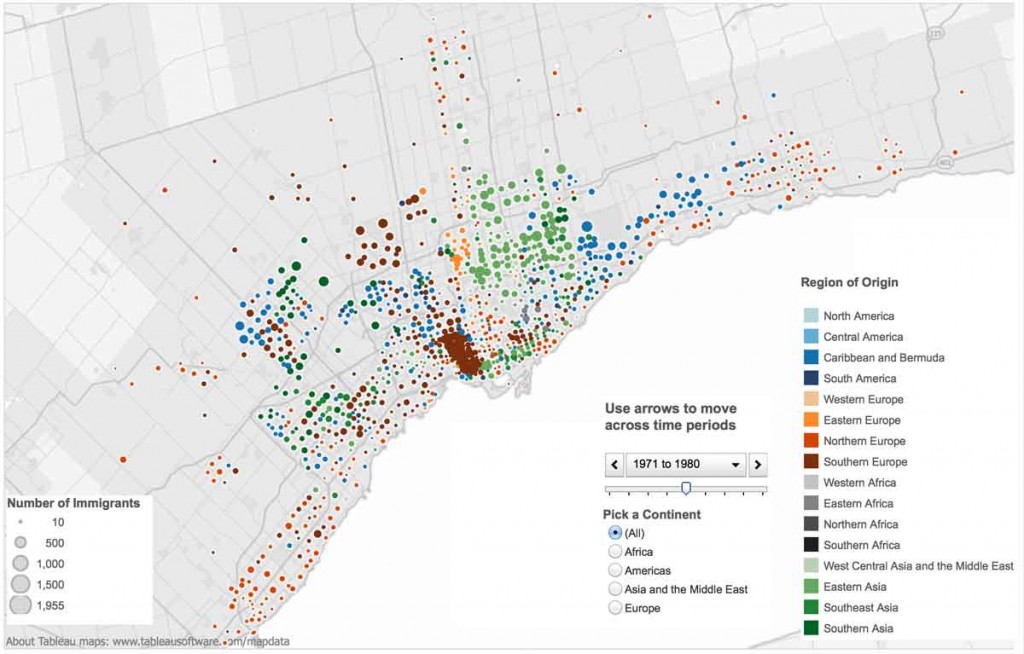

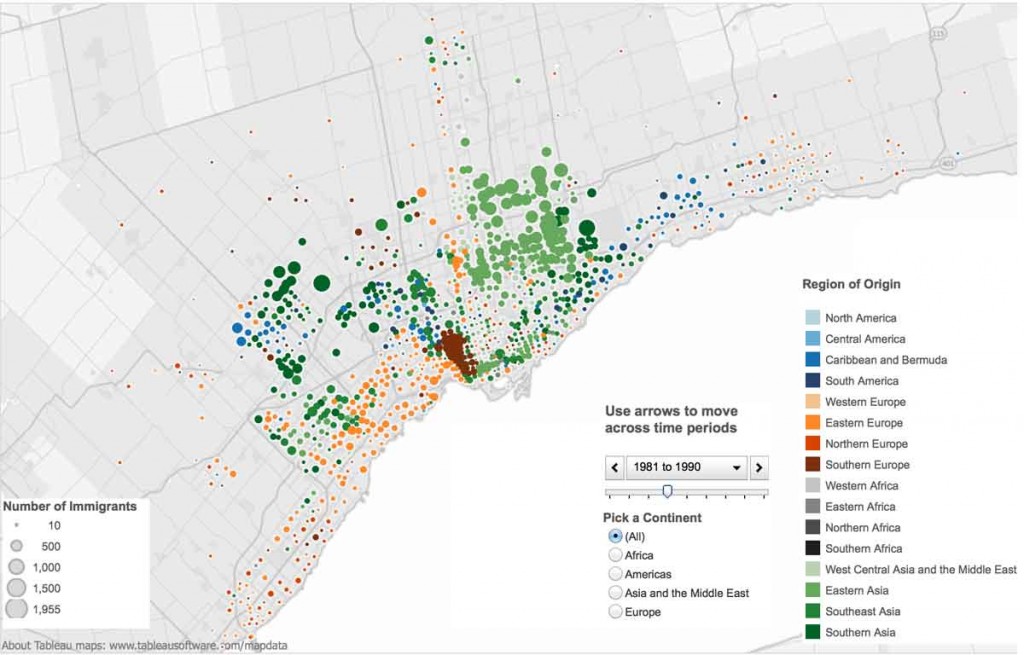

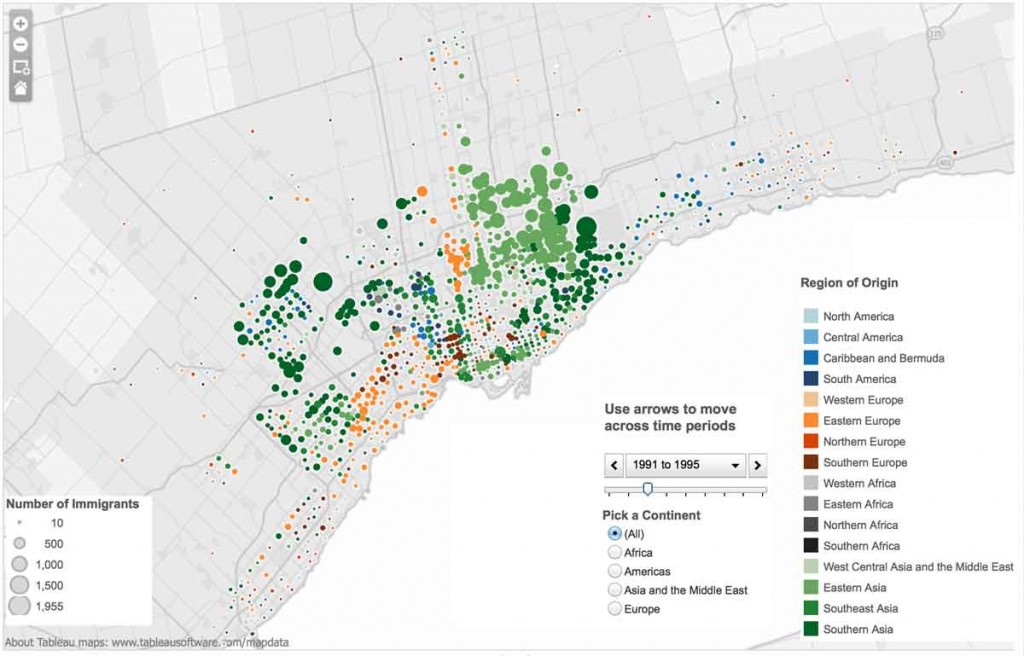

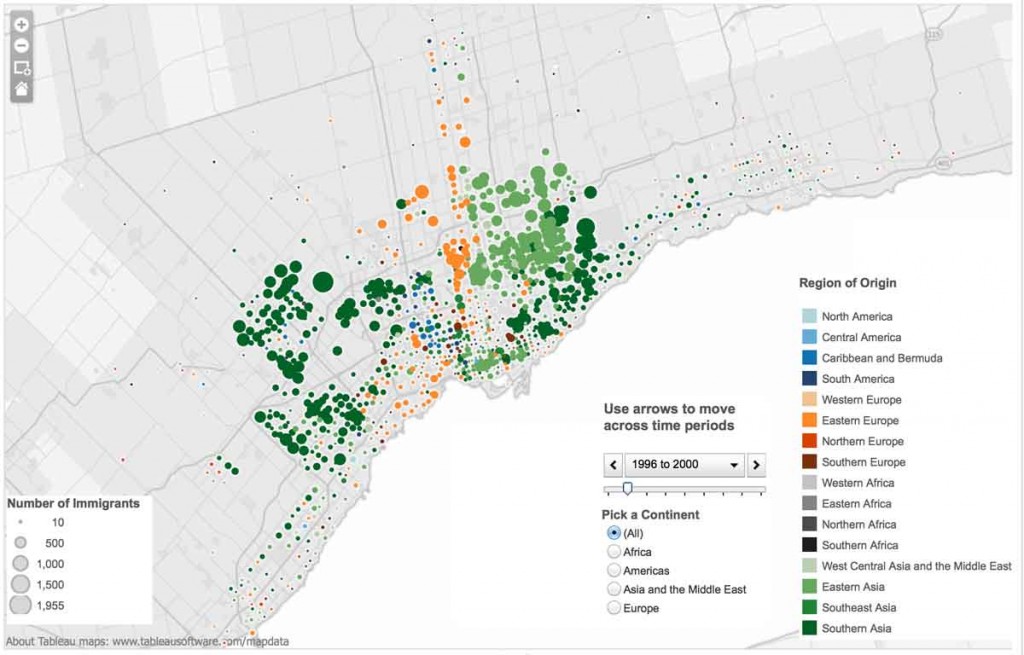

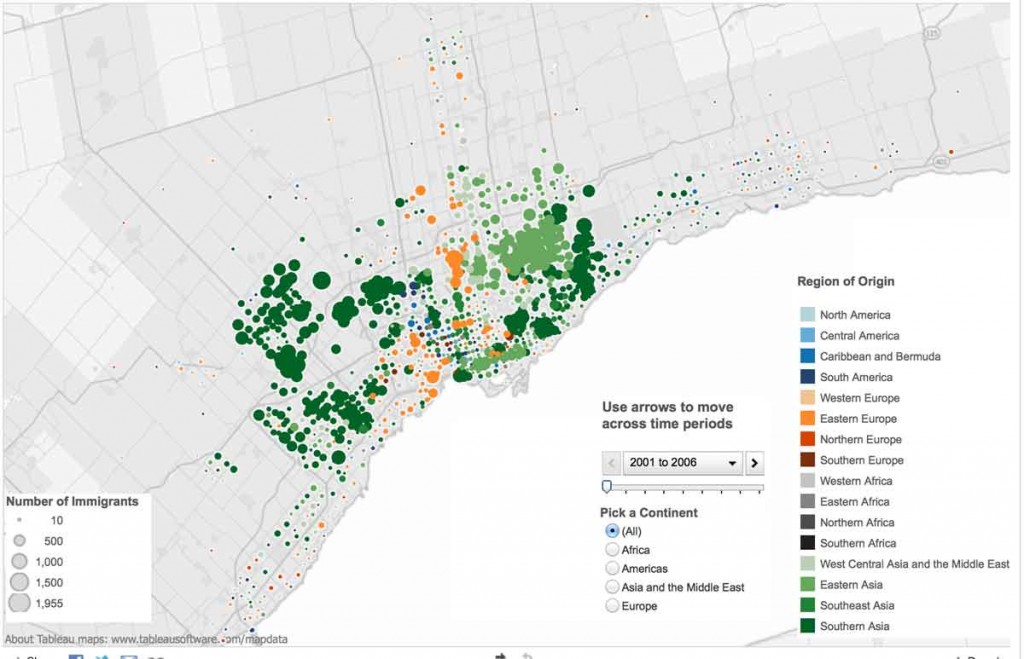

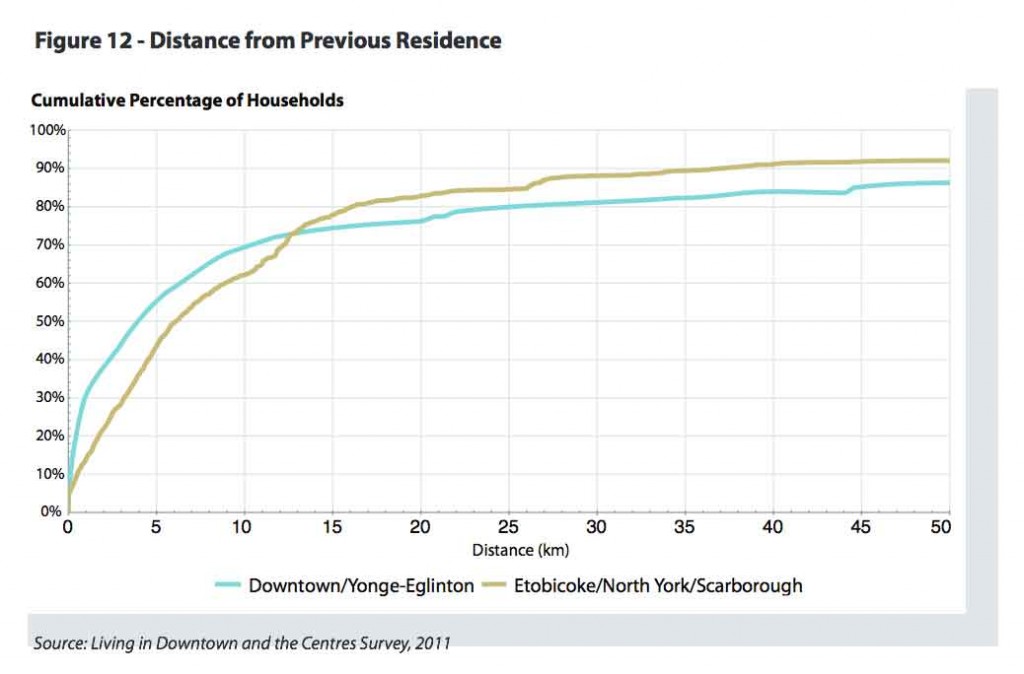

About 1970 the federal government removed previously restrictive immigration policies, in effect opening Canada to the world, and at the same time increasing the annual number of immigrants to about 200,000. Ever since and each year about half those immigrants have come to the Toronto region (about 3 million), and since Metro was almost built-up by 1975 this has driven the growth of the outer suburbs.

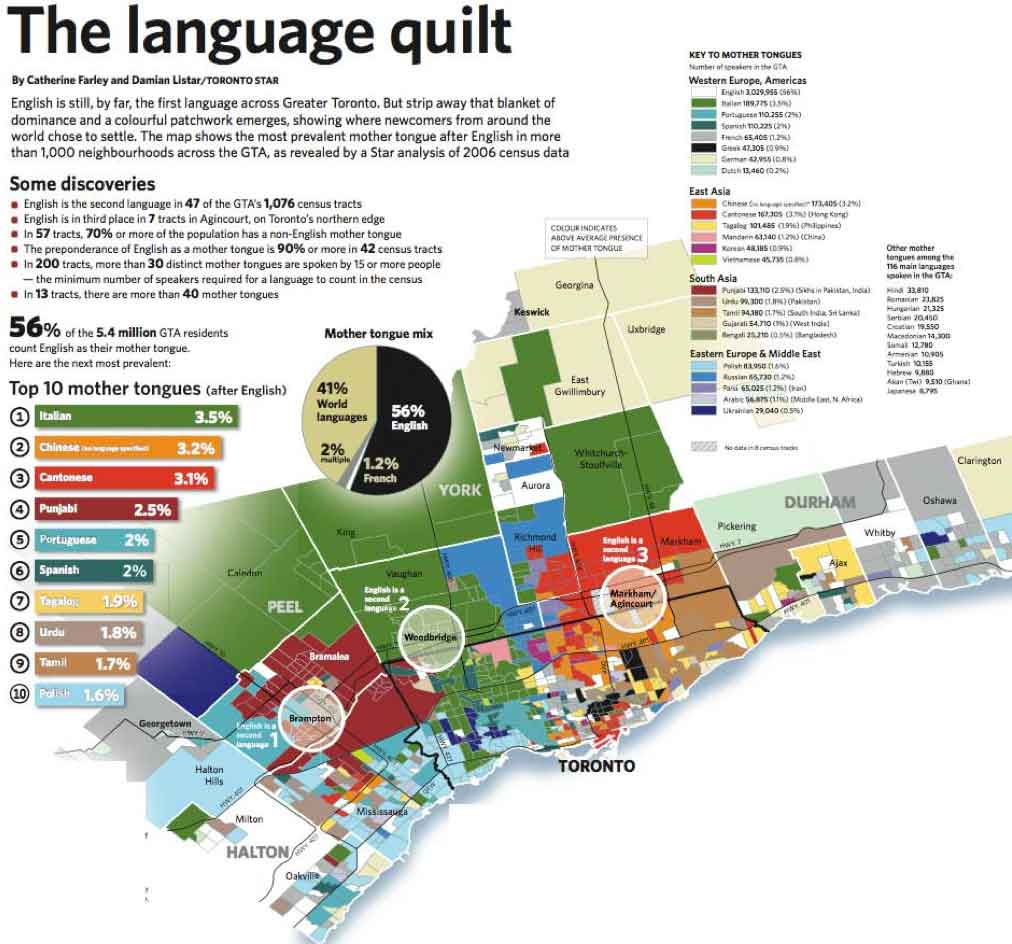

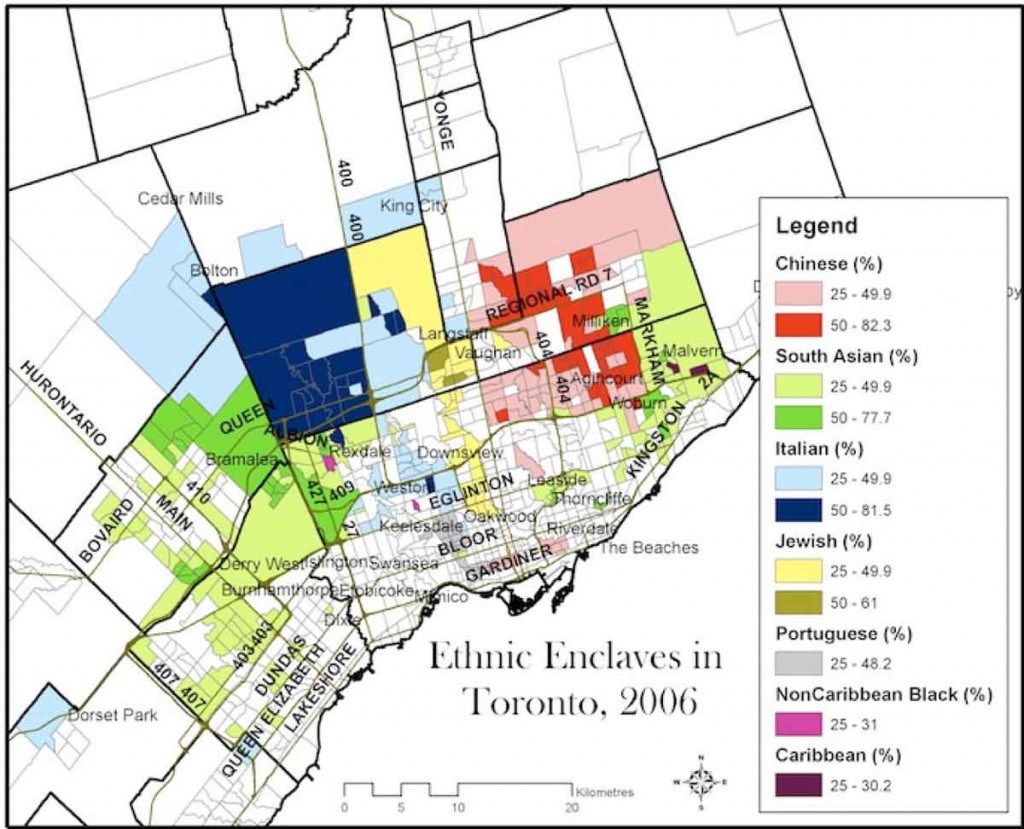

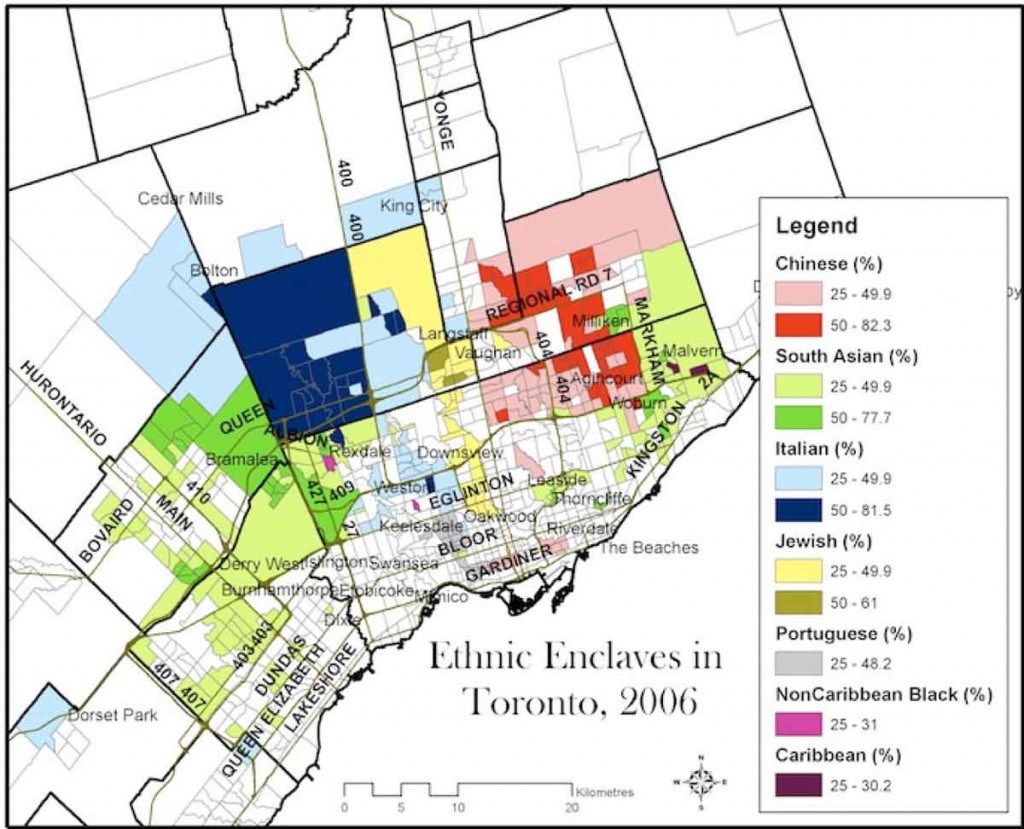

This map by Mohammad Qadeer of Queen’s University illustrates both the growth and the ethnic diversity of the outer suburbs. Most of the strong colours are in the outer suburbs – a map of population change since the 1970s has the same pattern, as does a map of visible minorities. Some outer suburban growth has been because of groups moving out of the City – most obviously the Italian and Jewish populations shown here, but many immigrants now go directly to the outer suburbs. In either case, the post-1970 outer suburbs have a population that is no less diverse than that of the City, and in in the north-west and north-east the proportions of foreign born residents are well over 60%. Overall the resident of the Toronto metropolitan area are about 50% foreign born, the highest proportion of any metro area in North America (or Europe), and the proportion of visible minorities is only a few points lower. Concentrations of the white populations are found in a corridor adjacent to Yonge Street north to the border of the old City and in the south west part of the new City; otherwise beyond the outer suburbs shown in this map diversity tends to decline with distance from the City of Toronto.

This map by Mohammad Qadeer of Queen’s University illustrates both the growth and the ethnic diversity of the outer suburbs. Most of the strong colours are in the outer suburbs – a map of population change since the 1970s has the same pattern, as does a map of visible minorities. Some outer suburban growth has been because of groups moving out of the City – most obviously the Italian and Jewish populations shown here, but many immigrants now go directly to the outer suburbs. In either case, the post-1970 outer suburbs have a population that is no less diverse than that of the City, and in in the north-west and north-east the proportions of foreign born residents are well over 60%. Overall the resident of the Toronto metropolitan area are about 50% foreign born, the highest proportion of any metro area in North America (or Europe), and the proportion of visible minorities is only a few points lower. Concentrations of the white populations are found in a corridor adjacent to Yonge Street north to the border of the old City and in the south west part of the new City; otherwise beyond the outer suburbs shown in this map diversity tends to decline with distance from the City of Toronto.

Ethnic diversity is reinforced by a diversity of suburban forms. The outer suburbs are structured around about thirty distinctive centres, some of them former villages that have become local tourist attractions, but several of them major suburban downtowns. These are edge cities except that they are not on the edge but in the centre of their municipalities, have concentrations of civic amenities such as city halls, and are rigorously planned.

Top left are the Absolute Condominiums, nicknamed the Marilyn Monroe towers, in part of Mississauga downtown – they were voted the best skyscrapers in the world for 2012 by the German firm Emporis.com. Top right is the downtown core of Mississauga – the building with the clock tower is the Civic Centre, the towers are mostly condominiums. Bottom left is downtown Brampton, a late-19th century small town being redeveloped as the core of the municipality. Bottom right is downtown Markham, a new urbanist, greenfield development still under construction, with a bus rapid transit system running on a dedicated right-of-way.

Between the various centres are patches of residential development, (and employment districts and other uses), many of them with modest houses on small lots, that reach to a precise but temporary urban growth boundary. This photo shows the western edge of Brampton. This sort of clean edge was used by Metro, keeping the provision of services and development in tight lockstep. When needed, the edge is extended by another band of the megagrid, which can be seen here outlined by arterial roads.

Between the various centres are patches of residential development, (and employment districts and other uses), many of them with modest houses on small lots, that reach to a precise but temporary urban growth boundary. This photo shows the western edge of Brampton. This sort of clean edge was used by Metro, keeping the provision of services and development in tight lockstep. When needed, the edge is extended by another band of the megagrid, which can be seen here outlined by arterial roads.

The overall density of the metropolitan area of Toronto is about 7000 people per square mile, roughly equivalent to Copenhagen or Stockholm. In North America Los Angeles is close to this, Chicago and Portland are about half.

Regional Plans

My sixth and final set of comments is about regional plans. Growth of the sort shown in the photo above has been relentlessly pushing outwards for the last 30 years as the regional population has grown between 80,000 and 100,000 per year. In the 1990s the province was alerted to the fact that this beginning to impinge on the environmentally sensitive areas of the Niagara Escarpment and the Oak Ridges Moraine, respectively to the west and north of the metro area. After a decade of discussions and proposals, in 2006 the province passed legislation implemented three regional plans that will govern urban growth for the foreseeable future.

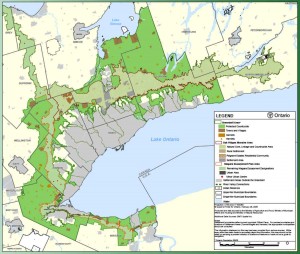

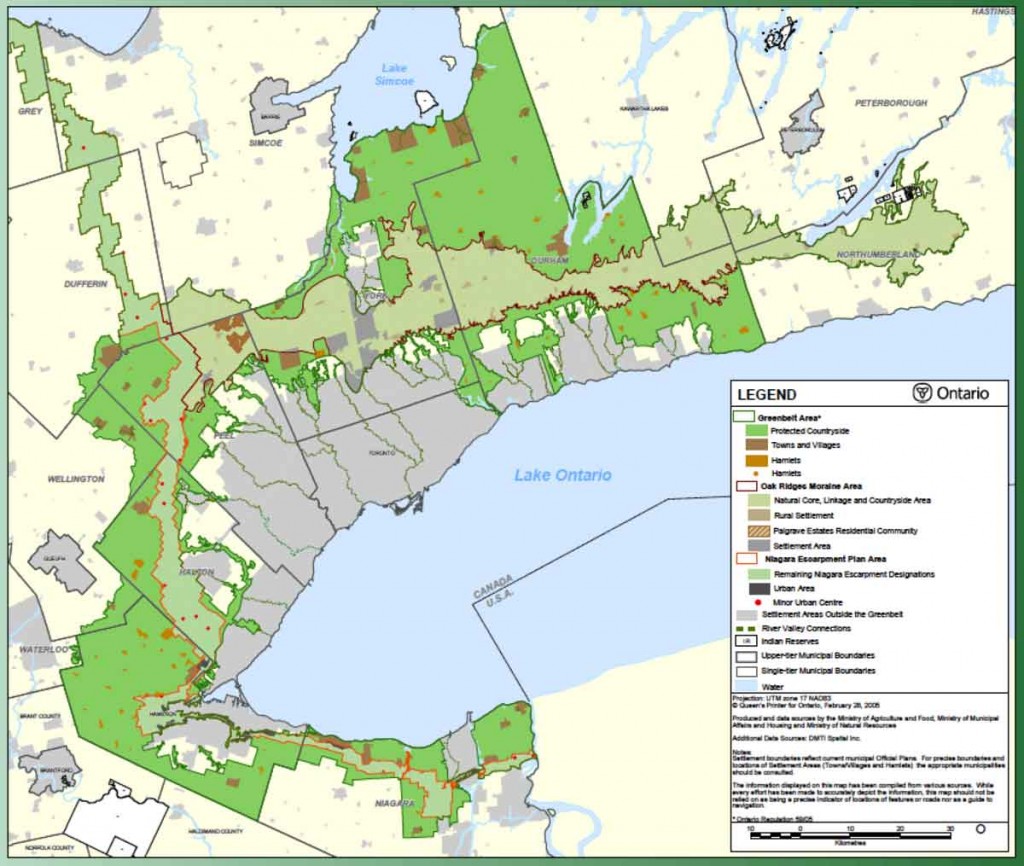

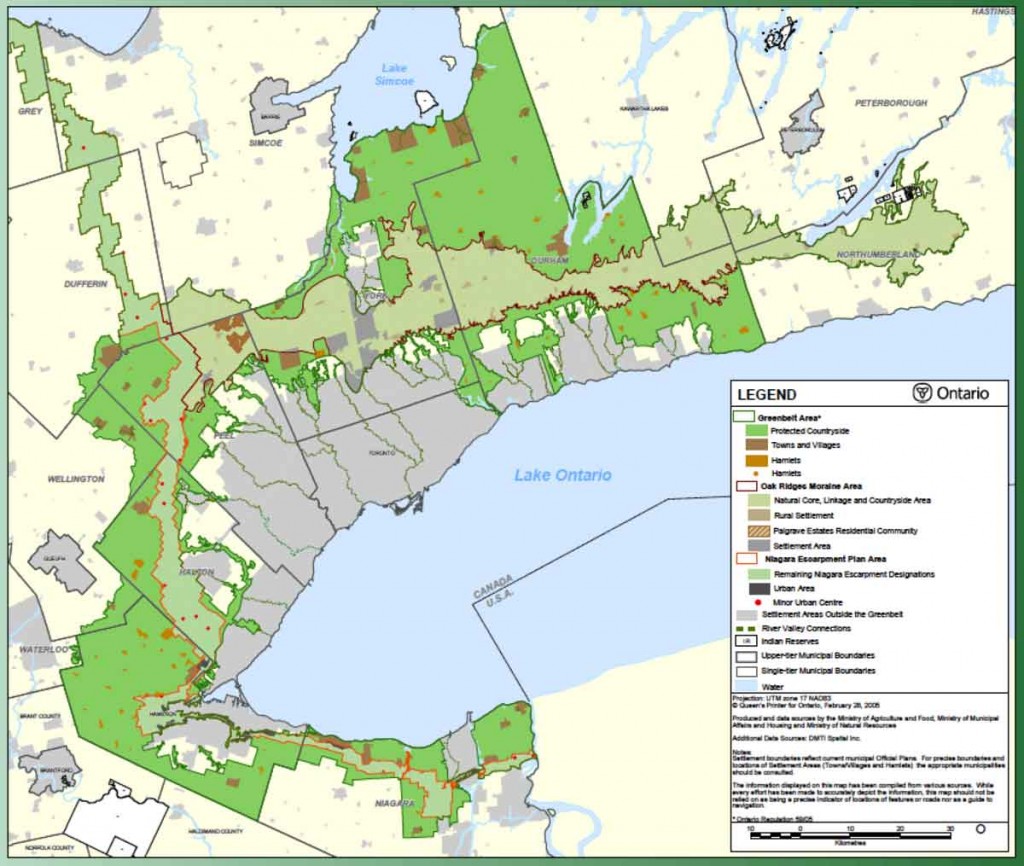

The first was the Greenbelt Plan, which identifies those environmentally sensitive areas and some adjacent ones as “areas where urbanization shall not occur.” It effectively wraps a corset of green around the metropolitan area.

The first was the Greenbelt Plan, which identifies those environmentally sensitive areas and some adjacent ones as “areas where urbanization shall not occur.” It effectively wraps a corset of green around the metropolitan area.

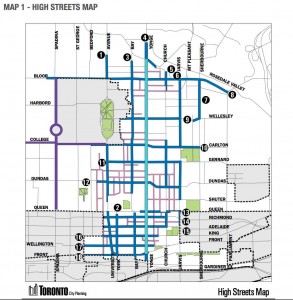

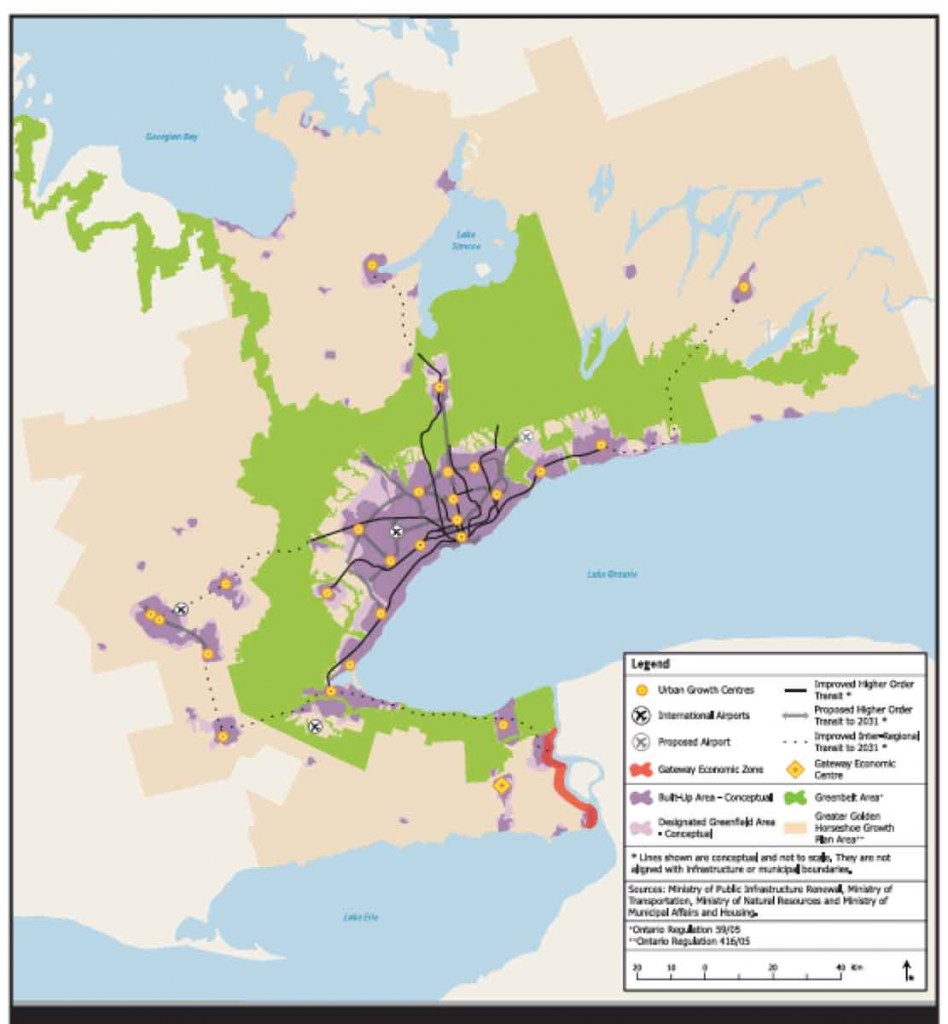

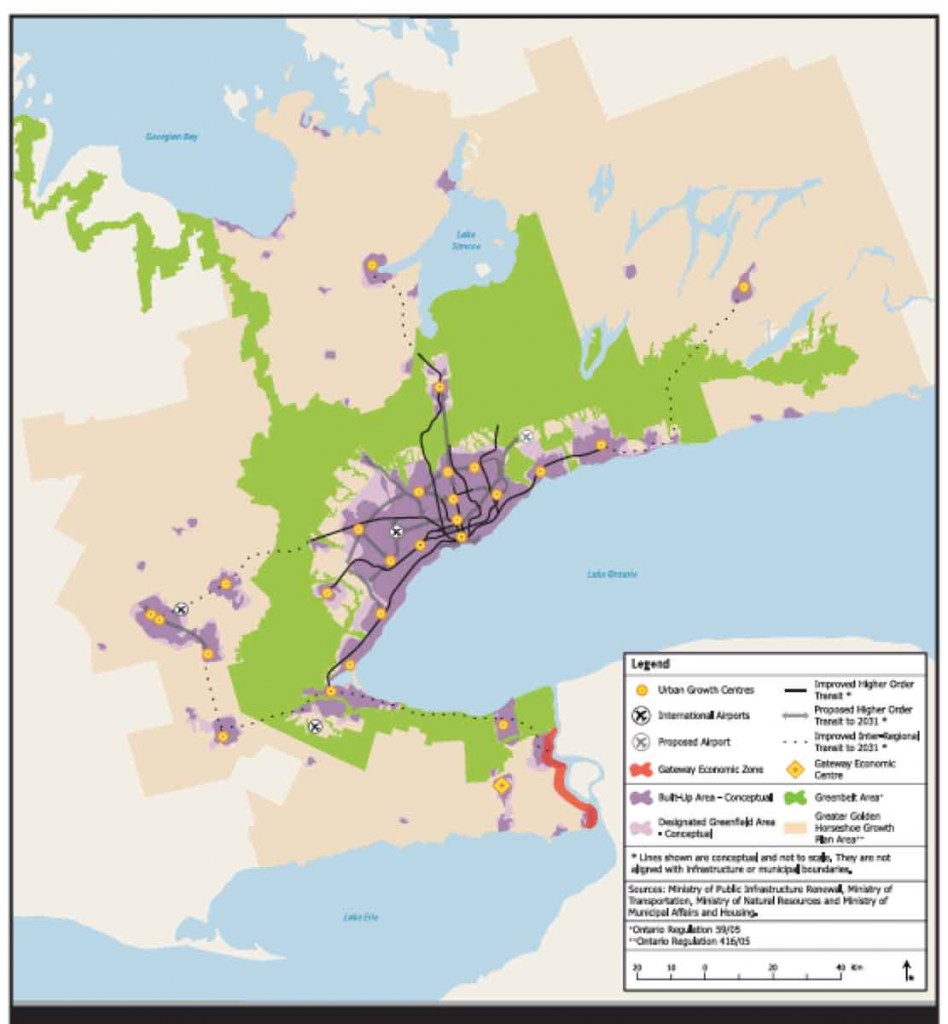

Nevertheless, population and urban growth asa result of immigration will continue. So the second plan, The Growth Pl an, identifies targets for intensification everywhere, specifies 25 urban growth centres for especially high levels of intensification, and extends the planning region beyond the greenbelt to an area that extends from Lake Huron to Niagara Falls.

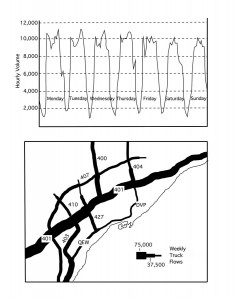

The third plan, called The Big Move, is for transportation planning, especially transit. The map above, though it is from the Growth Plan shows part of what the Big Move proposes – improved higher order transit along regional rail routes. At a more detailed level, the Big Move also emphasizes the role of light rail. There is to be very little new investment in roads and expressways. The idea, of course, is that with intensification transit will become more viable, and the more transit will promote intensification.

It is intriguing that after about 70 years of intense planning, the apparent model for future development and redevelopment throughout the region seems to be the sort of transit-supportive urban form that was created in the essentially unplanned industrial old City of Toronto.

Concluding Remarks

A question posed by the organizers of the conference in order to direct my presentation was – in what sense is Toronto an American city? In terms of planning I think Toronto has generally tended to head off in opposite directions to US cities – for the first 150 years by scarcely planning anything, and in the last 70 years through increasingly comprehensive municipal and now regional planning. One consequence, especially obvious in the high rise apartments throughout the metropolitan area, is that overall densities are substantially higher than most American cities. In spite of these differences there is no question that many of Toronto’s urban landscapes have a strong family resemblance to those in the U.S. – a testament perhaps to the fact that the power of international trends in making urban landscapes can mask considerable local differences in planning, and also support for the astute observation of Torontonian Marshall McLuhan that every city is now a suburb of every other city.